Jan Potocki – A Traveler of Infinite Imagination

/Jan Potocki, ca. 1810, photo: Wikipedia, public domain

In the history of Polish literature, few writers are as mysterious, multidimensional, and tragic as Jan Potocki (1761–1815), the author of The Manuscript Found in Saragossa—a work that has become legendary, inspiring filmmakers, philosophers, and poets, while turning its creator into an almost mythical figure.

Potocki was an aristocrat whose lineage traced back to the great hetmans and magnates of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was born in Pików, in the Podolia region—a land belonging to the old borderland tales, filled with steppes, manors, Cossack legends, and a tapestry of diverse cultures. Yet from the very beginning, his horizons extended far beyond the borders of his homeland. He was a man of the Enlightenment in the fullest sense of the word—a scholar, traveler, diplomat, archaeologist, ethnographer, and writer.

Between Science and Adventure

Potocki studied in Lausanne, attended lectures in Geneva and Paris, and then set out on journeys that took him across almost all of Europe and half the world—from Spain to Morocco, from Egypt to the Caucasus. His reports from scientific expeditions, especially his studies of the peoples of the Caucasus, testify to the remarkable openness and curiosity of a man who sought to understand the world in all its diversity.

He was one of the first Poles interested in anthropology and comparative linguistics, studying the languages and customs of the peoples he encountered. Yet in his travel notes there always lingers a note of melancholy—a sense of transience and the fragility of human experience.

“The Manuscript Found in Saragossa” – A Labyrinth of Meanings

From these experiences emerged his greatest work—The Manuscript Found in Saragossa. It is a frame narrative composed of dozens of interwoven stories that form a complex labyrinth of dreams, adventures, and philosophical reflections. The protagonist, a young officer named Alphonse van Worden, travels through the mountains of Andalusia and finds himself in a world of mysteries, spirits, scholars, bandits, Kabbalists, and beautiful women.

Beneath this baroque construction lies much more than an adventure tale—it is a meditation on human nature, faith, and knowledge. Potocki, raised in the rationalist spirit of the Enlightenment, seemed to sense that reason has its limits and that true wisdom is often hidden beneath the mask of myth.

It is no coincidence that The Manuscript later fascinated such artists as Luis Buñuel, Martin Scorsese, and Francis Ford Coppola. The 1965 film adaptation by Wojciech Jerzy Has became one of the most beautiful and hypnotic works in the history of cinema. Scorsese called it “the most extraordinary film ever made.”

Jan Potocki – The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, 1847 edition, photo: Wikipedia, public domain

Jan Potocki – The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, 1847 edition, photo: Wikipedia, public domain

A Man Who Belonged to No World

Jan Potocki belonged to a world that was disappearing before his eyes. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had fallen, and he himself—despite serving various monarchies—never found a place where he truly belonged. It is said that he sank into a melancholy bordering on madness.

His death—by suicide, using a silver bullet he had cast himself from the handle of a sugar bowl—became a tragic symbol of the end of an era.

Jan Potocki’s Final Journey

On a December morning in 1815, in his estate in Uładówka, Podolia, Jan Potocki ended his life. He departed as he had lived — in the shadow of mystery, with a gesture full of symbolic meaning.

It is said that he crafted a bullet from the silver knob of a sugar bowl, which he asked the local priest to bless. Then, after prayer and receiving communion, he locked himself in his study and shot himself with a pistol. In this legend echoes the clash between Enlightenment reason and the darkness of the human soul. Some scholars believe that the story of the silver bullet is merely a romantic embellishment, yet no one doubts that Potocki’s death carried both dramatic and deeply symbolic significance.

He spent his final years in solitude, immersed in depression and mystical contemplation. Weary of a world he no longer understood, he sought solace in prayer and philosophy. His death marked not only the end of the life of an aristocrat and scholar but also the metaphorical closure of The Manuscript Found in Saragossa — a world where reality and fantasy intertwined, reason met madness, and light blended with shadow.

The Legacy of an Eternal Journey

Today, Jan Potocki remains a fascinating figure who defies classification. He was the Polish Don Quixote of the Enlightenment—a dreamer who sought to unite the worlds of science and poetry, reason and mystery. His life and work form a tale of an unending search for meaning in a world that had lost it.

Perhaps that is why The Manuscript Found in Saragossa continues to captivate generation after generation—for within it, each of us can find a fragment of our own journey, our own labyrinth of questions without end.

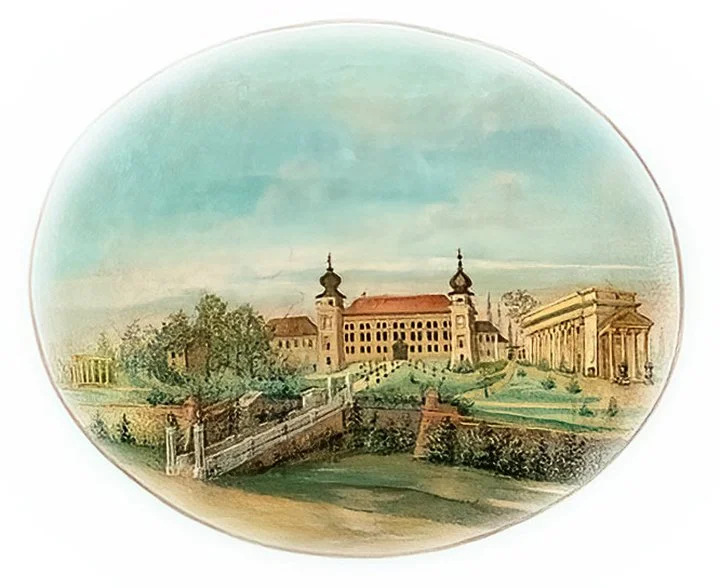

View of the Łańcut residence.

Wall painting from the late 18th century, created by artists from the circle of decorators working for Izabela Lubomirska, probably associated with Vincenzo Brenna’s workshop. Photo: Łańcut Castle Museum.

View of the Łańcut residence.

Wall painting from the late 18th century, created by artists from the circle of decorators working for Izabela Lubomirska, probably associated with Vincenzo Brenna’s workshop. Photo: Łańcut Castle Museum.

Biographical Note

Jan Nepomucen Potocki (1761–1815) — Polish aristocrat, writer, traveler, historian, and scholar of the languages and peoples of Asia and the Caucasus; author of the first Polish philosophical–adventure novel, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa. He studied in Switzerland and France, served in the Austrian army, and undertook diplomatic missions, including in Spain and at the court of Tsar Alexander I. Fascinated by Oriental cultures, he was a pioneer of ethnographic studies and historical geography.

Privately, he was married to Julia, the daughter of Princess Marshal Izabela Lubomirska of Łańcut. For the Princess’s private theater, he wrote the celebrated Parades. After the death of Princess Lubomirska, the Łańcut estate passed into the hands of the Potocki family. The memory of this remarkable ancestor was never forgotten in the Łańcut Castle—portraits, manuscripts, and memorabilia connected with Jan Potocki were carefully collected there.

In 2015, UNESCO declared the Year of Jan Potocki, marking the bicentenary of the death of the famous traveler and writer (1815–2015). Łańcut became the center of the commemorations, hosting the international scholarly conference Jan Potocki After 200 Years. On the day of the jubilee inauguration (June 25, 2015), a symbolic balloon flight was launched from the castle grounds, carrying commemorative mail—stamped and delivered by balloon—recalling Potocki’s own historic balloon flight.

In the Sculpture Gallery, an exhibition of illustrations to The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Sławomir Chrystow, commissioned by Marek Potocki, was presented. In November 2015, a new exhibition opened, featuring drawings inspired by The Manuscript…—including Potocki’s notebook, manuscripts, and a signet ring with the Pilawa coat of arms. Many of the exhibits were shown to the public for the first time, coming from both private and state collections in Poland and abroad. The Łańcut Castle Museum also prepared a special jubilee publication to commemorate the occasion.

Compiled by Joanna Sokołowska-Gwizdka

20th Austin Polish Film Festival, Texas

As part of the 20th Austin Polish Film Festival, audiences will have the opportunity to see Wojciech Jerzy Has’s masterpiece “The Manuscript Found in Saragossa.”

We warmly invite you to join us.