Color is a Vitamin

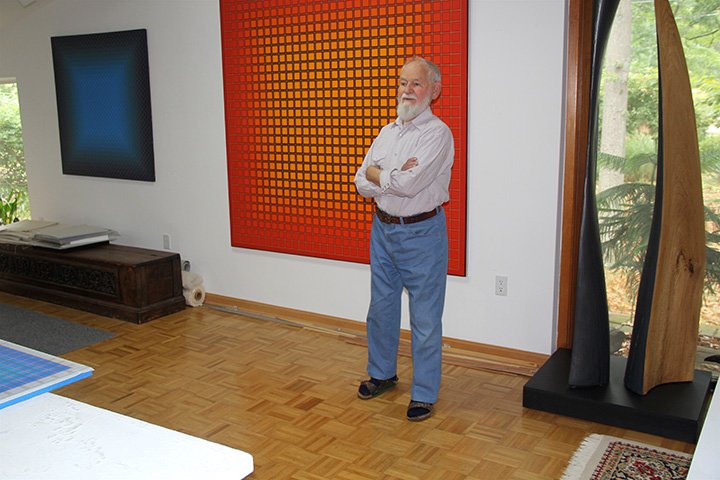

/Julian Stańczak

In the Studio

In an interview with Tomasz Magierski, the director discusses his documentary, 'Julian Stańczak. To Catch the Light'. The film delves into the mesmerizing world of Julian Stańczak, a seminal figure in the Op-art movement and a Polish-American artist renowned for his vibrant geometric patterns that play with perception.

Joanna Sokołowska-Gwizdka: During this year's Polish Film Festival in Austin, we will present your documentary film 'Julian Stańczak. To Catch the Light.' The film took 8 years to make. Why so long?

Tomasz Magierski: First, thank you very much for inviting the film to the festival. I am delighted that the audience in Austin will get to know the life and work of Julian Stańczak. I met Julian 8 years ago at a documentary film festival in Chagrin Falls near Cleveland. We met for dinner and discussed the potential film about him. A few months later, we conducted a three-day interview that became the foundation of the film's narrative, guiding our search for archival materials and shaping the film's concept.

At the same time, I was working on the documentary 'Przemyśl: Broken Dreams,' which reveals the unknown story of a teenage poet and writer, Reni Spiegel, who was murdered in Przemyśl in 1942. The film 'Julian Stańczak. To Catch the Light' is the second part of my Przemyśl diptych, describing the wartime tragedy of the Jews and the Siberian odyssey of Poles. Fortunately, these projects received funding from PISF (Polish Film Institute) and co-production from TVP1 (Polish Television) and FINA (National Film Archive – Audiovisual Institute).

The film presents the figure of a world-renowned painter, a representative of the art movement called Op-art, living in the United States but born in Poland, near Przemyśl. What about this artist captivated you so much that you chose to make a film about him?

Julian was born in Borownica, a village of a few hundred people. Later, the family moved to Przemyśl, where he attended primary school. At the age of 12, he and his family were deported to Siberia, and when I met him, he was already a retired professor from the Cleveland Institute of Art (CIA). So much happened in his life, not to mention art. Despite all of life's obstacles and dramas, Julian did not feel sorry for himself and had a lot of self-irony. His memories from the time of exile are from a child's perspective, not an adult filtering their memory over the years. This honesty in his account of his experiences led to the film's creation. Of course, it was also advantageous that Julian had a family album, which makes the film very personal. Art and his color theory are the film's second track, aiming to help the viewer understand his perspective on art and maybe start seeing the world differently.

In the film, we trace the protagonist's trajectory from Siberia, through wartime Africa, to the USA. With in-depth documentation that includes footage of General Władysław Anders, a key figure in Polish WWII history, and scenes of marching Junaks, a Polish scouting organization, did you make use of a significant amount of previously unreleased historical material?

The archival material concerning Russia is limited. Unlike the Germans, the Russians did not record their crimes. Most of the film archives come from the Sikorski Institute in London. I have a very good relationship with the Institute as I often use their materials, and this time they provided me with some photographs that I didn't even know existed. I also always use the collections of the Piłsudski Institute in New York, where I usually find the right photographs to tell the story. I must mention that these archival materials have never looked technically better than in our film, thanks to the work of our cinematographer, Maćek Magowski, who handled the post-production of the image. As for the paintings and family archives, Julian's wife, Barbara, has everything organized, and our collaboration with her has been and continues to be wonderful.

Julian Stańczak, as a child in Siberia, lost the use of his right hand. It's incredible that he learned to paint with his left hand. Did he discuss how, despite this disability, he chose to pursue painting?

It was a process. He wanted to play the flute, but that became impossible. I think that as a sensitive person, he wanted to find a way to express himself artistically. The disability only caused greater determination because he never wanted people to pity him. He also did not pity himself. At the beginning of our collaboration, we agreed that this would not be a film about a one-handed painter.

The painter gained fame after the "Optical Paintings" exhibition held at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York in 1964. It was at this time that the term Op-art was coined. Did this exhibition open a window to the world for him?

Certainly. A year later, there was another exhibition at MOMA, "The Responsive Eye," which resonated even more worldwide. Julian's paintings are now in most modern art museums and are still exhibited in galleries worldwide. Just a few months ago, his work was featured at The Mayor Gallery in London.

The artist served as a painting professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art for 38 years. Considering his significant contributions, how was Julian Stańczak's legacy commemorated in the USA following his passing in 2017?

In Cleveland, a mural Julian created in 1973 has been restored. Barbara discusses this restoration in the film. Additionally, in downtown Cincinnati, one can find a 100-meter three-dimensional piece by Julian adorning a building facade. Lastly, there are plans for a bust of Julian Stańczak on the grounds of the Cleveland Institute of Art, though the status of that project remains uncertain at this time.

Regarding the painter's wife, Barbara Stańczak, whom you mentioned, she runs a foundation in his name. What is the main objective of this Foundation?

The Foundation promotes Stańczak's work, orchestrates exhibitions, and facilitates discussions on Op-art. Barbara is a sculptor and has always been Julian's primary art critic, so the foundation is in good hands. Next spring, there will be a major exhibition of Julian Stańczak's work at the Museum of Modern Art in Łódź. The Foundation is involved in this, and we will also show the film then. Another commendable endeavor of the Foundation is the publication of "The Stanczak Color Quarterly", a periodical updating readers on pertinent events and activities.

Did you befriend the painter? What kind of person was he?

It's hard to talk about friendship from a distance. I held immense respect for him. He trusted in my approach and the work I was doing. This trust is why he was so open with me, and by extension, with the audience and history, especially now that he has passed away.

Your film garnered an award at the Fates of Poles Festival in 2023. Could you share more about other screenings and the general reception of the film?

The film premiered in Cleveland at the CIA, where Julian spent many years teaching. It was attended by professors, students, and even Siberian deportees. At a recent screening in New York, a 100-year-old former gulag prisoner, Mr. Fryderyk, drove himself from New Jersey. Such screenings are always interesting to me because if people are moved by the film, they open up with their experiences, which is always intriguing for me as a documentarian. We have also showcased the film across Poland at various screenings and festivals. Currently, we are in anticipation of its premiere on TVP1 (Polish Television).

Interviewed by Joanna Sokołowska-Gwizdka

Tomasz Magierski

Director of the documentary: 'Julian Stańczak. To Catch the Light'